What does the EUDR mean for farming and forestry?

What is the EUDR?

The EU Deforestation Regulation – known as the EUDR – is being introduced to ensure that the consumption of key commodities does not contribute to global deforestation. The new legislation is scheduled to apply from 30 December 2024 and applies to beef, palm oil, timber, coffee, cocoa, rubber and soy.

Why do UK farmers and foresters need to know about an EU regulation?

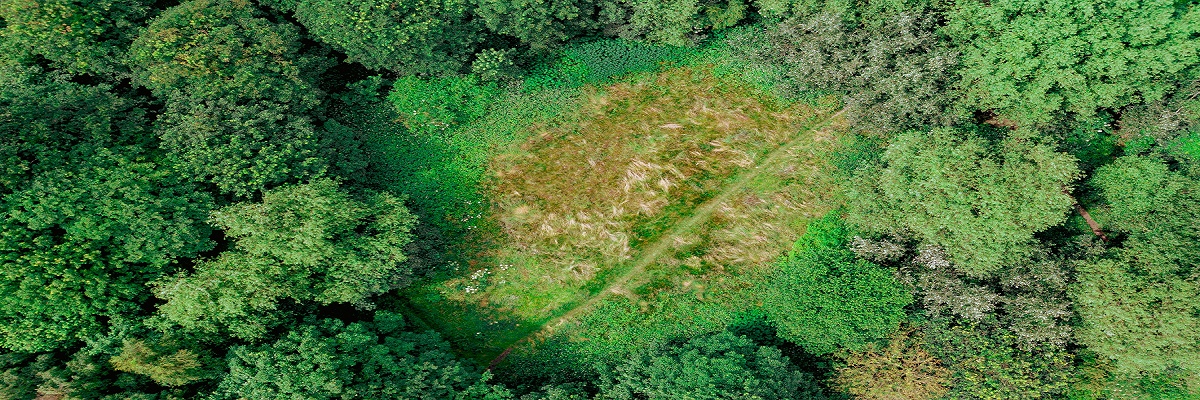

The EUDR has implications for any UK companies exporting any of the affected commodities into the EU market. They will need to demonstrate they have carried out due diligence checks to confirm that the products have not been sourced from land which was deforested or degraded after 31 December 2020.

For example, any companies exporting beef to the EU have been told they will have to provide geolocation coordinates as evidence that cattle have not been produced on recently deforested land. They will also have to demonstrate that the animals have not been fed animal feed that contains soy or palm oil that is driving deforestation abroad.

Forestry companies will have to complete a similar due diligence exercise, supplying evidence of the geolocation of the forest from which timber has been cut, along with details such as the date and time of production, species information, quantities and details of buyers and suppliers.

Keeping compliant and non-compliant commodities separate would be a challenge and so the supply chain is likely to want to meet the EU rules. In any event, the UK Government is also preparing to implement a Forestry Risk Commodity Regulation (UKRC), which has very similar objectives to the EUDR although its scope is slightly different. It aims to prevent the use of cattle products (excluding dairy), cocoa, palm oil and soy derived from illegally deforested land in UK supply chains.

Is the UK prepared for these new rules?

The UK’s felling licence regime already works on the principle of no net deforestation – when licences are issued they include replanting/restocking obligations. The majority of felled timber originates from forests certified to the UK Woodland Assurance Standard (UKWAS). This is endorsed by the Programme for Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) and Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification schemes. UKWAS is in the process of making changes to the standard, so it aligns with the EUDR requirements. They are also looking at the application of technology so they can meet the geolocation and traceability requirements.

However, although good progress is being made, the EUDR will potentially involve more bureaucracy for the forestry sector and associated costs. Producers who are not currently certified will face some significant hurdles as some timber processors are likely to want to satisfy EUDR requirements for all their suppliers if they are intending to supply to the EU market.

The UK imports about 80% of its timber requirements, although the bulk are softwoods tending to come from Scandinavia and North America where good governance arrangements are in place.

On the farming side of things, the Agricultural Industries Confederation (AIC) – the UK trade association for agricultural supply businesses – warns there are still uncertainties about how the regulations will be implemented.

Work is ongoing to try and ensure that any soy imported for animal feed meets the obligation by the start of 2025 through the UK Soy Manifesto. But the AIC says a lack of clarity about the regulations mean that the market for soybean meal has been affected, particularly for contracts from January 2025 onwards.

According to Sarah Baker, Head of Economics (Analysis) at the Agricultural and Horticultural Development Board (AHDB), provided the EU will accept the current traceability data for UK cattle, which includes geolocation data of holdings, but not individual cattle, as sufficient for EUDR compliance, it will not incur major costs or changes for the industry.

However, if the EU requires individual animal geolocation data, this will be costly and burdensome for an already stretched sector. A bigger challenge will be proving animals have not been fed soy from deforested areas. This requirement will also apply to any pigmeat or dairy beef exported to the EU.

She points out there is still confusion over whether exporters will need to prove if an animal has been fed deforestation-free soy for the whole of its life, or just from the point the regulations come into effect. It is currently impossible to get a forward price on soybean meal because of the uncertainty around the rules. Some producers are starting to look at alternative protein sources, but the assumption is that some soy is still going to be needed in the feed industry, particularly for the pig sector, which will impact farmers’ costs of production.

The British Agriculture Bureau, which represents the interests of UK farmers in Brussels, says there remain many questions over what information is required and lack of definitions which have not been answered.

The EU Commission has committed to the publication of an updated question and answer document by June 2024, which is expected to include more information on the framework. However, further guidance documents may not be available until later in 2024.