Q & A on carbon accounting for farms and estates

Jason Beedell, rural research director at Strutt & Parker, answers some common questions surrounding carbon accounting for farms and estates.

Are you aware of any work underway nationally to ensure there is a consistency of approach in assessing what carbon is being emitted and sequestered?

The methodology used by carbon calculators is now well-established and the data used to calculate the effects of different land uses and management practices is improving all the time.

A British Standards Institute (BSI) standard was being consulted on in late 2020 and should be in effect in 2021. Internet-based carbon calculators are potentially powerful tools which help people, organisations and communities to understand their energy use, identify trends and motivate them to reduce carbon emissions, assuming that robust information is fed into them in the first place.

Is it likely carbon accounting and valuing natural capital will have an impact on land prices in the future?

It seems likely that carbon accounting and natural capital will become more of a consideration, but as one of a whole range of factors affecting farmland values.

There are already many reasons why people buy land – many of which are not directly related to its ongoing profitability – but if markets develop for businesses to reduce and offset their emissions, this could offer another reason for people to invest.

An example scenario is where a large corporate business looking to offset its emissions could be in the market to buy carbon credits. Alternatively, farmers producing high value crops who want to show that they are ‘carbon neutral’ may want to use or buy other land as a carbon store.

This could be done by buying land for tree planting or entering into a long-term agreement with another land manager. Both will affect the value of the land.

Our forestry and farm agency teams have already seen large increases in interest for purchasing land for tree planting.

How do you calculate the carbon levels of soil and what are the costs associated with soil sampling?

Soil carbon levels can be obtained through a standard test available through most laboratories (Granta/NRM etc.). The test requires 300g of soil and costs around £12-15 per sample.

A number of samples will be needed to assess variation across a field. We recommend that regular sampling is done, to a scientific protocol, to help build up a picture of what is happening to organic matter and carbon levels across a farm.

It should be noted that there can be a huge variation between samples taken just centimetres apart, so monitoring soil carbon over time is not easy. But it can be helpful, as a starting point, to take samples from a couple of fields every year to begin building a picture of what is happening to carbon levels.

Do you envisage a market for UK farmers to trade credits from soil carbon sequestration or will increases in soil carbon be delivered through the agricultural policy framework/ payments?

A soil carbon trading scheme is a possibility, but I don’t think it will happen in the short-term. Soil carbon levels can fluctuate widely according to the time of year, land use and weather, which makes it hard to accurately record soil carbon sequestration consistently. This makes getting schemes paying for soil carbon difficult to get off the ground.

Do you think the new Sustainable Farming Initiative will help in terms of supporting farmers and landowners to cut carbon emissions from their activities?

We are still waiting for details of the Sustainable Farming Initiative (SFI) which Defra plans to roll out as a stepping stone to the ELM scheme in 2022. However, it is anticipated that it could offer payments to farmers to reduce emissions from fertiliser use and improve soil health which would have a positive impact in terms of carbon.

Is there a risk of double counting? For instance, a tenant and landlord submitting a return for the same farm.

There is a risk of double-counting, particularly in the landlord/tenant sector where both parties may be interested in utilising green resources. In reality, where a carbon calculator is only being used to measure and monitor the carbon balance, then there are no real consequences if double counting does take place.

Where it becomes an issue is where someone is selling carbon credits or completing an annual return as part of a scheme. Anyone intending to sell carbon credits must use a certified registry to register, track and permanently cancel credits. Where land is let, our recommendation would be that no credit sales can be agreed that extend beyond the term of the tenancy (much like an environmental agreement).

Logically where land is let, it should be the claimant for the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) who would be the beneficiary of any carbon credits and responsible for the carbon emissions associated with the land.

Our natural capital account assessments consider all estate assets, and separate out in-hand and tenanted GHG emissions and carbon storage.

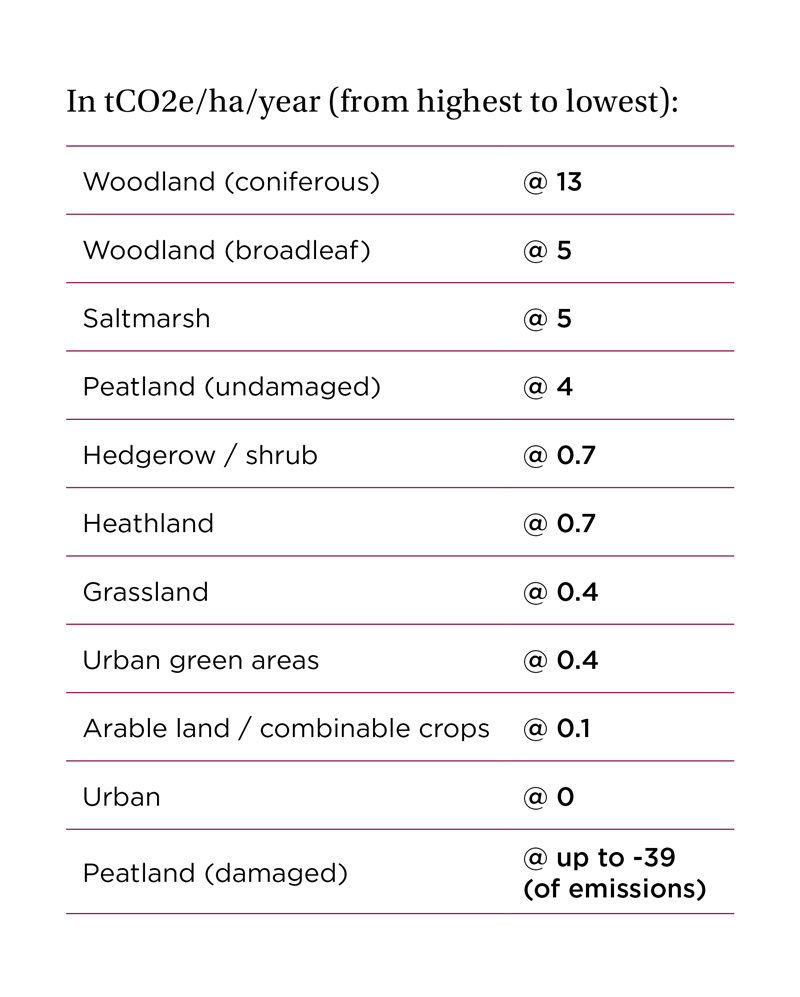

How much carbon do different land types sequester?

The rates below represent typical carbon sequestration rates. They may vary significantly depending on the type and condition of the land use. These are the rates used in the 2018 Committee on Climate Change report.

For woodland carbon credits, a much lower ‘net’ rate should be used to calculate potential credits generated to account for model uncertainty and a buffer in case tree growth is less than expected.

If you have further questions about carbon accounting or how to measure natural capital, then please get in touch with jason.beedell@struttandparker.com

This article is part of our Land Business Insights “Piecing together the rural carbon jigsaw”publication.