Practical ways to cut greenhouse gas emissions from farms

Reducing a farm or estate’s carbon footprint is a long-term process and, although it can feel somewhat overwhelming, there can be some quick wins.

There is arguably a simple answer to the question of what individual farmers should do to start their journey towards reducing their carbon footprint: Focus on improving technical performance.

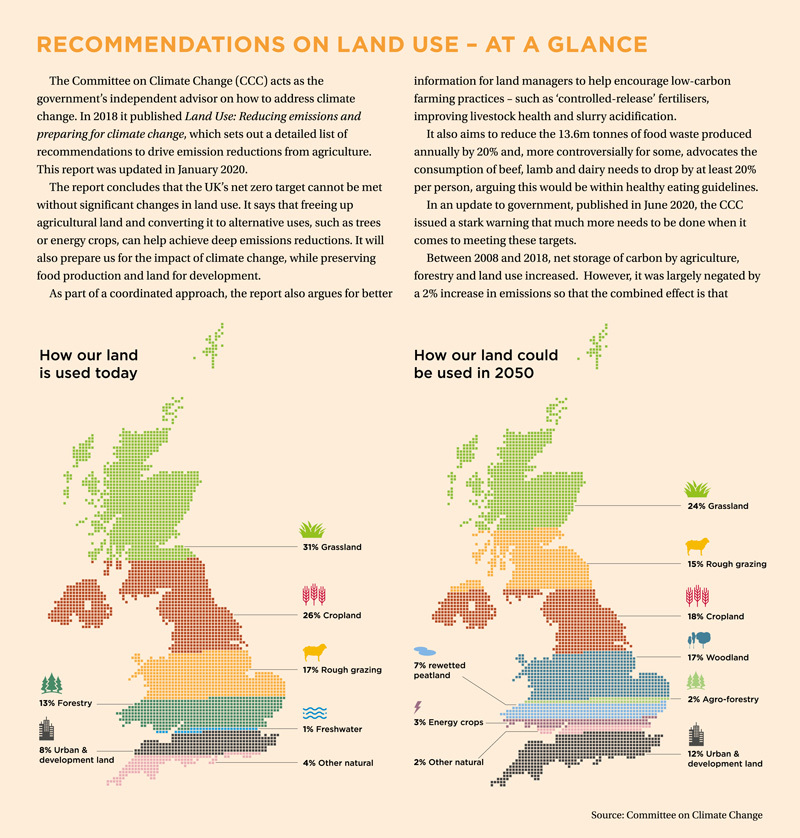

Much of the public debate about how agriculture can reduce emissions has focused on the Committee on Climate Change’s recommendations for changes to land use.

While this is significant at the macro level, and land use changes will be required to meet net zero targets, it is unlikely to be the starting point for most farmers in terms of how they approach the topic.

Land use change is not a decision to be rushed, so for many the focus will understandably be on improving technical performance to raise productivity.

Raising productivity to cut farm carbon

Improved productivity allows farmers to dilute their emissions per tonne of crop, kilo of meat or litre of milk produced, demonstrating they are using their resources more efficiently.

By doing this they may identify where there is potential for land to be freed up for alternative uses which are known to increase carbon sequestration, such as woodland or bioenergy crops.

The use of renewable energy sources is likely to be another central plank in any strategy to reduce agriculture’s emissions, securing savings through reduced electricity costs, while potentially generating new revenues for the business.

By making small improvements in technical performance across the board, farmers can become more efficient and reduce costs, while also helping the environment.

Measures to reduce rural carbon emissions

It is sensible to make changes to any farming system gradually to determine which practices are having the biggest impact and to protect margins. Factors other than climate change will also need to be considered when changing farming systems, such as the impact on animal welfare, pollution and biodiversity.

But examples of practical measures that farmers can take to reduce greenhouse gases by sector include:

ARABLE

Cutting emissions by Improving soil health

Soil is a farmer’s most valuable resource, and increasing the amount of soil organic matter improves its fertility, structure and water-holding capacity, which can have a positive impact on yields and its carbon sequestration potential. Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) is the carbon component of soil organic matter.

When soil is cultivated it causes the release of carbon dioxide into the air as soil organic matter oxidises. Reducing the amount of soil disturbance and moving towards lower-tillage systems can reduce this flow of carbon from the soil, but it will not suit all situations.

Where it does, wider benefits can include reduced establishment costs, less soil erosion and increased biodiversity.

The most obvious way to increase soil organic matter is through regular additions of organic fertilisers such as compost and farmyard manure.

Increased use of cover crops, grass leys and generally introducing greater crop diversity will also help to build up organic matter and improve soil structure.

Many of these strategies form part of regenerative agriculture, a farming system gaining traction in the UK which is based on the principle of implementing practices which regenerate the natural resources that have been depleted through intensification of agricultural systems. This helps reduce reliance on artificial fertilisers.

The starting point for measures to improve soil health should be soil testing so you understand your baseline.

Cutting emissions by improving fertiliser use

The bulk of greenhouse gas emissions from arable farming systems come from the use of inorganic fertilisers, so after improving soil health and fertility, optimising fertiliser applications to cut the amount needed without reducing yields can have a significant positive impact.

Most farmers achieve a nitrogen use efficiency of around 60%, but 80% is achievable – mainly through more scientific matching of the crop’s need with applications, taking action to reduce losses (through volatilisation and nitrification), and applying the right rate at the right time accurately.

This involves more targeted application of fertilisers in line with crop requirements and taking into account the previous and following crop.

Using precision farming techniques which allow for variable rate application of fertilisers will also help to improve efficiency and reduce wastage. Switching away from urea to fertilisers with a smaller carbon footprint is another possibility. The government is currently consulting on restricting the use of urea fertilisers anyway.

Timing nutrient application correctly is as important as applying the right amount. Applying fertilisers in warm or wet conditions can increase the level of nitrous oxide emissions significantly.

CATTLE AND SHEEP

Cutting emissions by improving animal performance

Beef and sheep account for a high level of greenhouse gases from the agricultural sector because of the process of enteric fermentation, where plant material is digested in the digestive tract releasing methane as a by-product.

There is currently debate about how to measure methane’s impact on global warming. While methane is characterised as a short-lived greenhouse gas in terms of its atmospheric lifetime (on average 12 years), the climate impacts of methane emissions are not: it takes over 700 years for the temperature change effect of a pulse emission of a tonne of carbon dioxide to rival that of a pulse emission of a tonne of methane.

Some scientists argue that stable methane emissions make no further contribution to warming and should not be penalised. Others make the point that a constant level of emissions may lead to no additional warming beyond current levels, but it does lead to more warming than if the methane was not emitted and current warming has already transformed our planet and its natural systems.

If animals are reared, the best approach to mitigating greenhouse gases in the beef and sheep sector is currently to focus on improving overall animal performance by looking at genetics, feed efficiency, growth rates, fertility and disease control.

For example, selecting animals which can be finished more quickly will cut the amount of methane that animal produces during its lifetime. Focusing on health planning and fertility will maximise the number of calves and lambs reared per animal, which reduces emissions per kg of meat produced.

Cutting emissions by improving manure storage and handling

How animal manure is stored and spread can have a significant impact on the amount of methane, ammonia and nitrous oxide it produces. Storing manure heaps on an impermeable base and covering with sheeting helps to reduce losses, as does improved timing of fertiliser applications and avoiding excess application.

DAIRY

Cutting emissions by improving forage quality and feeding

High-quality forage is fundamental to a dairy business, underpinning the physical and financial performance of the herd. A focus on improving forage quality, by picking the right grass varieties and through timely operations when silage-making, can encourage intake, boosting yields and reducing the amount of bought-in feed required. Switching from a feed like soya, which has a high carbon footprint, to alternatives with a similar protein content can be another option for reducing emissions, although this will depend on the rest of the ration.

The science is still developing as to the effectiveness of reducing methane production from cows through changes in the diet. There is some evidence that the inclusion of some legumes, such as white clover, in forage might have an impact on reducing the amount of methane. Agricultural scientists at the University of California reported in 2019 that they had found that a certain species of red algae seaweed reduced emissions for dairy cows by more than 50%. Meanwhile, researchers from Penn State University have recently reported they saw emissions reduce 16-36% when they added the compound 3-Nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) to a dairy diet, with the product acting as an inhibitor to the enzyme that causes methane production.

Cutting emissions by improving manure handling

Timely application of slurry – using low-emission spreaders such as trailing shoe and injection systems – has been shown to significantly reduce emissions of nitrous oxide. Having slurry and muck storage systems which minimise ammonia losses into the atmosphere is also important. Grant funding is available for slurry store covers, through the Countryside Stewardship Scheme, which also keep rainfall out of the store, reducing the quantity of slurry that needs to be stored and spread.

Cutting emissions by improving nutrient use

As in the arable sector, targeting and applying manures and fertilisers in line with crop requirements is a good strategy to help to reduce fertiliser use and improve yields.

PIG AND POULTRY

Cutting emissions by reducing energy requirements

The pig and poultry sectors have a lower carbon footprint than beef or sheep, but there is still scope to reduce emissions. Such systems often have a high energy requirement associated with heating and ventilation systems so renewable energy options are already common. Further gains can be achieved by investing in the performance of buildings through insulation and more efficient lighting.

ENERGY

Cutting emissions by improving energy efficiency

Reducing energy usage and increasing energy efficiency is a central policy aim across all types of property, so looking at energy consumption across the whole farm and estate is important. Assess energy use in domestic, rented and business premises to identify areas for savings, especially in larger, older properties. It is generally cheaper to save energy than generate it.

Cutting emissions by increasing renewable energy production

Further investment in renewable energy may be worth considering, particularly where on-site consumption of electricity is high. While renewable energy subsidies have almost disappeared for new installations, the technology has advanced greatly over the past decade, so costs in many areas – notably solar – have fallen considerably.

Grant support for low-carbon farming

England

In England, there have been three rounds of the Countryside Productivity Small Grants (CPSG) scheme which has provided funding for projects which improve productivity in the farming and forestry sectors. The last of these rounds closed for applications in November 2020.

The CPSG offered grants of between £3,000 and £12,000 to support farmers who wanted to invest in specific pieces of agricultural equipment.

All the items included in the scheme were identified as ones that would help farmers achieve improvements in either animal welfare, resource efficiency or nutrient management.

Defra has confirmed that the third round was the final time that farmers would be able to apply to CPSG, but it has also pledged that grant support will continue to be available to farmers in future.

The government is planning to introduce two new productivity grant schemes as part of a Farming Investment Fund to provide financial assistance to support farmers to invest in equipment, technology and infrastructure that boosts their productivity and delivers environmental and other public benefits.

Scotland

A pilot Sustainable Agriculture Capital Grant Scheme was announced in September 2020 offering farmers in Scotland grants of up to £20,000 to buy equipment that will help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support sustainable land use.

Capital items supported by the scheme included a range of livestock handling systems, weighing equipment, EID devices, calving detectors, precision-farming equipment, low-emission slurry application systems, slurry store covers and very flexible tractor tyres.

The funding provided by government was based on standard costs for such items. Applications closed on 11 October 2020.

This article is part of our Land Business Insights “Piecing together the rural carbon jigsaw”publication.