How to avoid common pitfalls when planting new woodland

When it comes to woodland creation, there’s a question you should ask yourself long before you get to the detail of designing a woodland and that is: What is its purpose?

All too often, when it comes to lowland broadleaf woodlands, people can approach the process the wrong way around, focusing on the size and design before fully considering the objectives. Your starting point should always be the desired goal, and the design should reflect and enable that. Objectives could, for example, include boosting biodiversity, creating a space for recreation, a livestock shelterbelt or a riparian feature. Alternatively, you might be driven by a desire to play your part in mitigating climate change, facilitating a farm diversification or building an income such as woodland carbon.

Focusing on such outcomes from the outset will help you ensure the design is fit-for-purpose, efficient and appropriate for the landscape, rather than attempting to be ‘all things to all people’ – a sign of which is often an underperforming woodland with an overwhelmingly diverse species mix.

The concepts of ‘diversity’ and ‘resilience’ are vital in considering species choice, but this doesn’t automatically necessitate the use of a huge list of species. Fearing regulatory pushback, the temptation is to throw in ever-more species in ever-decreasing quantities, simply to hedge bets and garner approval. Better, instead, to select, say, 10 well-chosen species based on sound research, the local landscape, yield, soil and climatic conditions, that you know will not only survive, but thrive.

Losses are expensive and frustrating and, if you’re growing with the Woodland Carbon Code (WCC) in mind, the reality is certain species will give you a better yield (growth), and therefore carbon unit return, while others will only yield minimally or not at all. As an outcome, planting trees to accrue carbon units under the WCC is a perfectly legitimate goal, but you need to build this outcome into the design from the outset, otherwise the potential carbon and subsequent financial return will be considerably lower than it could have been.

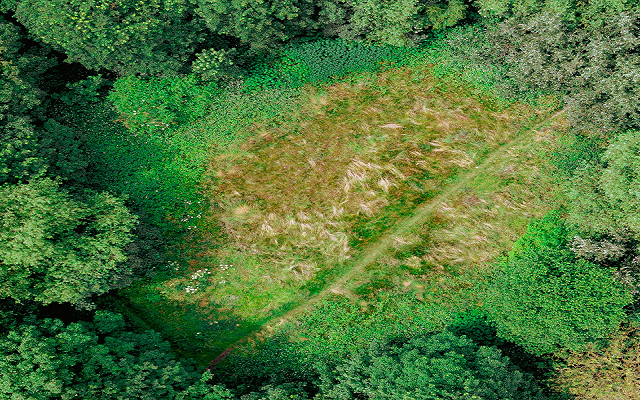

Part of the challenge is the wide range of considerations when choosing what to plant, given the increasing numbers of pests and diseases and the current – and expected future – impact of climate change. Also factor in the grant money available and the potential prize of carbon value and the danger is that, in trying to hit so many objectives, you end up with a woodland that will deliver mediocre growth, be susceptible to damage or loss – and ultimately not meet your intended objectives. A new woodland should integrate smoothly within its surroundings by reflecting local species and intimately connecting to nearby woodlands, hedgerows, or habitats, rather than standing isolated at the edges of a field.

In Scotland, there has traditionally been a tighter emphasis on species choice directed by woodland type, commercial productivity and stand resilience. However south of the border the drive is more for smaller broadleaf woodlands that focus on biodiversity, community access and resilience and, laudable as such goals are, they have led to some ill-considered projects that are likely to cost more to manage than they will ever generate.

To marry purpose with good design, you should seek specialist advice from a forester from the outset. With reference to the Ecological Site Classification tool from Forest Research, they will investigate soil types, topography and slope, plus local micro-climate considerations and how much – if any – peat is in the soil.

Before you get into this level of detail however, remember that initial question: What am I trying to achieve? The answer is unique for every single project and the design, therefore, needs a similarly individual approach.

This article first appeared in our latest issue of Land Business. For more download the Autumn/Winter 24 edition of Land Business.