How can warm words on forestry be turned to positive outcomes?

Congratulations are due to the organisers of the National Forestry Conference 2023 held in Newbury in October, on the theme of The Next Generation – Securing Our Future.

Given the parlous state of nature, the ever-changing climate and the essential targets of net zero, this was an apt title. And what a part that trees and forests, and all the wide range of professionals, interest groups and sectors thereby involved, can play in helping to create and manage sustainable forests that deliver to society’s pressing needs.

The importance of forestry was highlighted right from the start by Dame Glenys Stacey of the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP). Established in 2021 and with a remit for England and Northern Ireland, it seeks to “protect and improve the environment by holding government and public authorities to account”.

She was, she said, following the delivery of woodland targets and strategies with great interest and a keen eye. And so she, and the OEP, must do. A positive rhetoric is not always being matched by positive outcomes. Figures released by Forest Research for 2022 / 23 show that new woodland creation in the UK was 7% lower than the previous year, the value of timber imports has increased, and the woodland bird population has fallen by 34% since the 1970s.

Other figures are more optimistic – timber exports are up and employment in forestry over the last year has increased by 10%. Technically, the UK is also now the third largest importer of timber when it was previously the second largest importer. However, this ‘improvement’ can’t really be considered a success as we have merely been overtaken by the United States and the level of imports remains at around 80% of our timber requirements.

Perhaps most tellingly, in a UK Public Opinion of Forestry Survey, 84% of respondents agreed that “a lot more trees should be planted in response to the threats of climate change”. I take this as meaning that society is looking for forestry to provide sustainable solutions – but of course forestry owners need to benefit from this too. Warm words and thoughts do not pay the bills and woods do need to be financially viable as well as great places to walk in and enjoy.

In her address, forestry minister Trudy Harrison reiterated the commitment to action and delivery on the government’s targets. She highlighted the government’s Environmental Improvement Plan (EIP) 2023. The EIP is an update of the Government’s 25 Year Environmental Plan, which seeks to ensure that its aspirations and targets are maintained over the 25-year timescale, regardless of which party is in government. And this gets to the nub of many forestry and environmental matters – it is a sector which requires commitment, consistency and time. A personal view is that commitment and consistency have long been largely absent, and time is in short supply given climate change means there is no time for procrastination.

Now I like much of what the minister says – she is well briefed, concise, speaks with passion and is clear on the desired outcomes. So, it was great to hear that she is focusing on the lack of timber being used in construction (timber is used in a staggering 90% of new builds in Scotland whilst only 9% in England). Additionally, a grey squirrel action plan is to be launched and a venison strategy, in relation to deer management, is to follow. The statement that “venison should not be seen as an elite meat, but served to patients and prisoners” does, I hope, set a goal.

The minister also highlighted a statutory instrument due in 2024 on Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) that will make a positive impact on woodland creation. We shall see – recent policy changes appeared to dilute the impact of BNG.

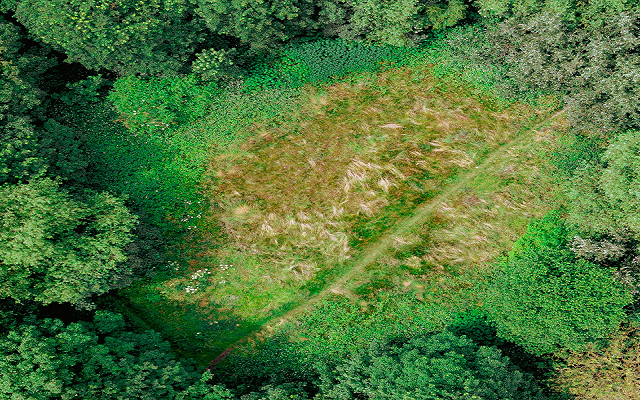

Positively, the unhelpful binary approach to ‘broadleaves or conifer’ is evolving into an entirely welcome and sensible consensus that more of both are needed to be planted and managed. Data from satellites and remotely operated drones is making data easier and cheaper to gather, thereby enabling greater monitoring accuracy and supporting evidence-based management options. Tree breeding – for so long one of the paupers of the forest research sector – has developed longer term funding and is producing qualified and tested seedlings that are more climate and disease resilient and give trees better form. All this is all good news.

However, let’s have a dose of realism too. Governments and ministers can and do change. The next election is less than 18 months away. The minister left the audience with a challenge – “what would you want me to do?”.

So, I pass this on to all readers of this blog post: what would you want the forestry minister to do? Do let me know and we can use these ideas to approach the minister. Moreover, as the government cannot, and should not, be the sole driver of change, these ideas will be a welcome challenge to us too.