Building resilience within the rural estate

There is an ancient Chinese proverb which says: ‘When the winds of change blow, some people build walls and others build windmills.’

With rural estates and farms on the brink of a period of rapid transformation, how businesses choose to respond to the ‘winds of change’ may prove to be the difference between those that thrive and those that merely survive.

A radical shift in agricultural support, following the introduction of the Agriculture Act, is inevitably top of the list when it comes to explaining why change in the rural economy is expected.

Subsidy reform comes as no surprise – it’s been talked about constantly for the past five years and marks the largest change in policy for the agricultural sector since the MacSharry reforms of the early 1990s.

But minds have been focused now that cuts to Basic Payments have finally become a reality – at least in England – and are being implemented more swiftly than many had anticipated.

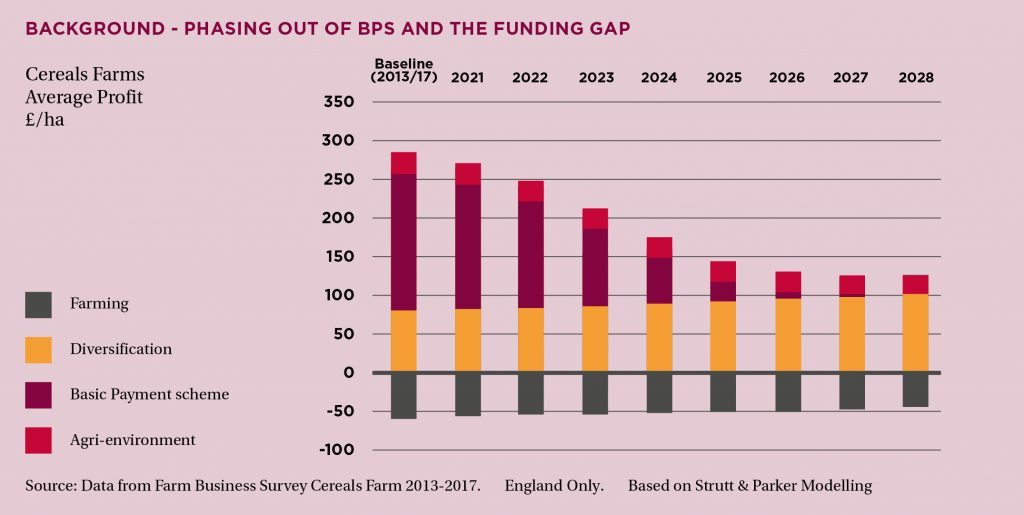

We now know that larger farms (those claiming more than £150,000 in annual subsidy) will see two-thirds of their Basic Payments disappear by 2024.

Strutt & Parker’s modelling work shows that this is likely to have a significant impact on farm profits. Businesses sitting in the middle 50% or bottom 25% of performance could see their net profits fall by as much as half by 2028, even assuming they sign up to the new Environmental Land Management (ELM) scheme to recoup some of the shortfall left by the loss of BPS.

This points to income from in-hand farming operations or let agricultural portfolios coming under increasing pressure in a relatively short period of time. At its simplest, by 2028 many farms and estates need to have found alternative income streams worth about £85/acre – the equivalent of a lowland BPS payment – simply to stand still.

Mosaic of change facing rural estates

However, while the biggest shift in agricultural support for decades is hugely significant, it is not the only revolution facing those who run land-based businesses.

Landowners are facing a ‘mosaic of change’, with a combination of factors coming together with the potential to have a profound influence on how they manage land and property to derive an income from it.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have temporarily diverted attention away from the climate change emergency and the natural environment, but they remain a high priority.

There is a growing expectation from society that farms and estates will play their part in cutting emissions, increasing carbon sequestration, tackling flood risk, improving air and water quality, and reversing declines in biodiversity.

Important socio-economic changes are also at play, including the digital revolution, demographic shifts and changes in the way we all live. COVID has accelerated changes in our working practices, with the success of video platforms such as Zoom raising questions about the necessity of working from a city office five days a week. Lockdown has also given everyone a much wider appreciation of how access to green spaces improves health and wellbeing.

So what does this mean in practice for the future direction of estates?

For many landed-estate owners this will naturally be a worrying time. However, there are good reasons to believe rural estates can have a vibrant future.

Of course, sustainable food production will remain at the heart of the vast majority of land-based businesses. Whatever our environmental and social ambitions, the nation still needs feeding and there is strong public support for UK farmers to keep producing to provide food security. But alongside this, the rural sector has the potential to provide solutions to some of the big challenges facing society which is an exciting opportunity for entrepreneurial land-based businesses.

Environmental agenda facing rural estates

In England, Defra plans to reward landowners for better environmental management through the Environmental Land Management (ELM) scheme which will incentivise people to farm more sustainably, create space for nature, enhance animal health and welfare, and reduce their carbon emissions.

The ELM scheme will undoubtedly be a useful first step in terms of driving change and helping landowners on the journey of monetising the provision of public goods, while reducing their environmental footprint.

But few expect ELM support to fill the funding gap left by the phasing out of Basic Payments. The bigger opportunity for rural estates, according to many, lies in providing ecosystem services through the management of natural capital to the private sector. Large corporations are coming under increasing pressure to offset their own carbon emissions and are looking for innovative ways to do this responsibly.

For example, we are already talking to corporate companies who are exploring the possibility of forming joint ventures with landowners to create new woodlands.

These are businesses that have no desire to own the land, but are prepared to enter long-term partnerships with landowners to plant woodland, in return for stakeholders being able to walk in the woods and for them being able to use the initiative for marketing purposes.

It is possible that in the next 10 years we could see corporate companies wanting to put their names to woodlands, which can be enjoyed by their stakeholders, in much the same way that they currently sponsor sporting and music stadiums.

Rural estates and trading businesses

For those estates currently reliant on agricultural, commercial and residential rents, the creation of, or partnership with, new trading businesses is perhaps the most obvious answer when thinking about building business resilience.

Farm Business Survey data shows total income from diversified activities in 2019/20 was £734m, with an estimated 68% of farm businesses that took part in the survey having some sort of diversified activity.

However, when the letting of buildings for non-farming uses is excluded from this dataset the percentage of farms with some sort of diversified income falls to below 50%, with just 6% engaged in enterprises like tourism accommodation and catering, compared with 22% with solar energy.

To date, the rural sector has only scratched the surface of possibility when it comes to introducing diversified enterprises and we expect to see others following those early adopters, as is the case in any innovation adoption life cycle.

What those businesses might be will vary between estates and according to the asset base, the owner’s aspirations, location and unmet needs within local communities. Those who have already diversified into the hospitality or events sector will understandably be feeling bruised by the current crisis, but that does not mean that the principle of diversification is wrong.

For some owners, with the right entrepreneurial skills, diversification will mean the launch of their own in-hand businesses. But for others it could be better to invite others that share their values onto the estate to work alongside them as tenants or trading partners.

Having the self-awareness to know which camp you should be in will be vital. Shared values – with trading partners and your customer base – will be crucial as we move forward. The work of leadership expert Simon Sinek has shown that customers buy from businesses that hold the same beliefs and values that they do. Having absolute clarity on why you want to diversify your estate business and faithfully following through on this inspiration can be a source of competitive advantage.

This ties in with perhaps one of the most significant changes that an estate looking to build resilience may need to implement over the coming years – the need to position itself positively within its local community and be bold and clear in terms of what it stands for and what it is providing.

There is currently increased public scrutiny of the distribution of wealth – in particular, the source of inherited wealth. As land ownership is one of the most conspicuous faces of inherited wealth, landed estates are under the microscope like never before. There is also much greater public interest in the environmental impact of land use.

How those at the helm of these businesses respond to that is important if they are to position themselves as modern and relevant.

Changing perceptions

A rural estate which understands how it is perceived and is prepared to engage proactively with the local community to understand its needs, desires and concerns will put itself in a stronger position moving forward.

Many estates do already have a positive story to tell in terms of the social value they can bring – creating employment, business opportunities and providing activities which contribute to people’s sense of wellbeing. However, we as landowners can often fail to fully articulate this contribution.

We also need to turn up the volume on what we are doing around managing natural capital and the provision of habitats.

But how does an estate go about creating a strong story?

We know more and more people want to enjoy guilt-free experiences which come when they feel they are engaging in activities with a low carbon footprint and are aligned to the environmental agenda.

This opens up an opportunity for an estate to create its story, for example, around how it has planted trees to make wildlife corridors, which produces a habitat that supports a particular species of flora or fauna.

The estate might then provide public access to those wildlife corridors and encourage members of the public to enjoy the leisure opportunities associated with them. If people identify with the ethos of the estate, they are more likely to support a coffee shop, or pay a premium to base themselves in an integrated workspace on it.

The ESG credentials of rural estates

Even estates who have no desire to welcome the public through the gates – perhaps focusing on the provision of ecosystem services to corporate buyers – are likely to find themselves needing to give more consideration to how they are perceived externally and the social and environmental value they deliver.

Companies that recognise the importance of being able to prove their own Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) credentials will be most likely to be able to attract investment from the corporate world.

The emphasis on ESG and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has become noticeably more pronounced within the business community in the past few years and responsible investors view this as far more than a tick-box exercise.

An example of this is growth in the B-Corp movement, which is a certification scheme for companies focused on balancing purpose with profit. The scheme acts as a guarantee to consumers and business partners that a company is meeting the highest standards of verified social and environment performance, public transparency and legal accountability.

Such initiatives may feel alien at the moment – only two farms have signed up to B-Corp so far – but embracing them may help to open doors. We are already having conversations with companies outside of the rural sector who are grappling with ways to offset their carbon footprint and are open to the idea of buying carbon credits from estates engaged in projects such as woodland creation or peatland restoration.

It feels like companies which can demonstrate their environmental and social value, and really leverage their estate’s story and heritage, will have scope to attract premium rates for carbon credits.

Shift in mindset

The path that each estate takes to build resilience over the coming years will be individual. In addition to the ideas already outlined there may be opportunities in providing land for Biodiversity Net Gain habitat banks, selling nitrogen credits and collaborating to deliver environmental improvements at a landscape scale.

Some businesses may choose to focus on making changes within their farming operations, by implementing regenerative farming methods or through the use of data to help drive business performance. Others will want to look at investing in housing, workspaces and renewable energy projects to help support the development of their local community.

The rural sector is embarking on a new era, but there is strong potential for businesses to derive a profit from the natural environment and the provision of other public goods.

With a shift in mindset, the rural sector should be well-placed to play a key role in delivering on the green agenda, creating jobs and homes, and improving public health.

Estates which understand the power of their own brand and are forensically focused on what the market wants will be at the front of the queue when it comes to unlocking these new opportunities. They might not choose to build windmills, but they certainly won’t be choosing to build walls.

This article is part of a wider Land Business Insights publication on The Future of the Estate. Navigating the changes that lie ahead for rural estates will require innovative thinking and a proactive approach. The team at Strutt & Parker is here to help you on that journey, working alongside you to evaluate your options and turn plans into action. Please do get in touch if you would like to talk about any of the report’s contents.